Victorian Apothecary

Rated 5.00 out of 5 $ 5.00 Select options 5.00 Select options; Lavender Dreams $ 10.00 Add to cart Unicorn Dreams $ 10.00 Add to cart Snowberry $ 10.00 Add to cart Dragon’s Blood Soap. Victorian Apothecary Labels, 23 Medicine Bottle Decals, Pharmacy Tag, Halloween DIY Labels, Digital Download Sheet, Druggist Decals, 371Q RarePaperDigitalShop $ 3.95. Old Fashioned Apothecary Labels, General Store Bottles, 20 Whiskey, Bourbon & Wine Labels, Medicine Cabinet Decor, DIGITAL DOWNLOAD, 953. Late 19th Century English Victorian Antique Apothecary Cabinets. View Full Details. 19th Century Mahogany and Oak Apothecary Cabinet. Dutch Pine Apothecary Cabinet, 1950s. Located in Nijmegen, NL. This Dutch apothecary cabinet was made circa 1950s in the Netherlands. It features four large drawers with metal cup handles. Victorian Apothecary Digital Collage Printable Art, Medicines and Poisons, You Print Wall Art DigitalButterflies. From shop DigitalButterflies. 5 out of 5 stars (287) 287 reviews $ 4.00. Favorite Add to Custom Perfume - Victorian Fragrance Blends - Make Your Own - 15ml TheParlorApothecary.

An apothecary is making up a prescription, whilst another takes a jar down from a shelf. Engraving by C. Luyken, 1695. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection (CC).

Who were the apothecaries and what role did they have in medicine?

Apothecaries were a branch of the tripartite medical system of apothecary-surgeon-physician which arose in Europe in the early-modern period. Well established as a profession by the seventeenth century, the apothecaries were chemists, mixing and selling their own medicines. They sold drugs from a fixed shopfront, catering to other medical practitioners, such as surgeons, but also to lay customers walking in from the street. Their daily tasks- as distinct from those of a barber-surgeon or physician whose primary duties during this era involved related diagnosis and treatment- were thus defined by a focus on retail (sales to the public without performing other clinical roles). Their shops were designed to attract the customer, and they stored their wares in elaborately decorated jars which looked beautiful in store. Skill in chemistry was an important part of the apothecary's identity, and these jars- which contained the ingredients used to manufacture medicines- leant prestige to their craft.

These practices were broadly comparable across Western and Northern Europe at this time, but in colonial North America medical treatment was patchier, and the distinction between different types of medical practitioners was looser. Missionaries or settlers who were pharmacists at home brought their craft with them, but they were relatively few and far between. Some colonies lacked apothecaries entirely, and physicians often dispensed their own drugs. Medicine was also often practiced by lay people, such as churchmen and governors, or housewives

A figure made up of components of the apothecary trade. Engraving by N. de Larmessin II, 1695. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection (CC).

In England, on the other hand, apothecaries had become organised under a professional body by the early 1600s, hoping both to prevent other practitioners stepping into their jurisdiction, and to establish legitimacy of practice. The Worshipful Society of Apothecaries (founded in 1617) had begun to regulate training through apprenticeship. The Society of Apothecaries also established a chemical laboratory for the manufacture and sale of its own drugs to society members in 1672, in order to control the production of medicines and to boost its members’ reputation for the sale of reputable remedies. In addition, the Society inspected drugs sold in premises in London, in an attempt to monitor and prevent adulteration of pharmaceuticals within the city boundaries.

Despite this, by the eighteenth century the distinction between apothecaries and physicians in England had become blurred. From the end of the 1600s, English apothecaries had been increasingly practicing patient treatment alongside the sale of medicines, acting as general practitioners and advising, prescribing or otherwise treating where a doctor had not already done so (for example, as surgeon-apothecaries). By doing so, they were stepping on the turf of the physicians. This generated a controversy that ultimately led to major changes within the apothecary profession in Britain, and meant that medical practice there developed differently than other Western countries such as France and (ultimately) the USA.

An apothecary and his apprentice working in the laboratory of John Bell's pharmacy. Engraving by J.G. Murray, after W.H. Hunt, 1842. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection (CC).

British law at the beginning of the eighteenth century enforced the monopolies of the tripartite system of medical professionals, and in theory regulated their activities. However, by this time the system was under pressure, and boundaries of practice were shifting. The low numbers of elite physicians in comparison with market demand for medical care meant that the public were turning to apothecaries as a more readily available- and cheaper- alternative. Due to this imbalance in care, as well as overcrowding amongst the apothecaries, the old hierarchy began to give way. A turning point came when the Rose Case of 1704 approved this custom in law and gave apothecaries the freedom to practice physic as well as pharmacy. Throughout the eighteenth century, English apothecaries therefore developed into a group calling themselves general practitioners (and indeed, resembling modern-day GPs), and divisions between the tripartite professions further broke down. By the end of the century, the surgeon-apothecary treated a wide range of social classes. As they were not educated to the same level as the physician (nor did they share their social status) they were a great deal cheaper and were thus used more widely by the general populace for medical care.

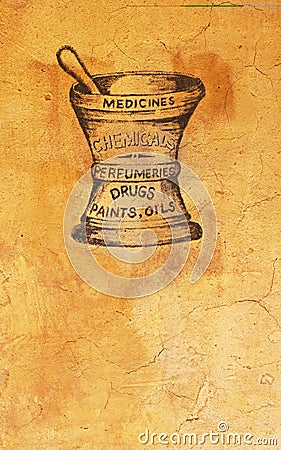

Victorian Apothecary Sign

By the 1800s the role of the apothecary had changed considerably. Whilst some apothecaries were still involved in the dispensing and mixing of drugs, few did so from a retail perspective and instead charged patients directly for remedies during clinical visits. The retail aspect of medical practice had now fallen to a separate group, the chemists and druggists. The Regency and Victorian druggists ran their profitable businesses from a street shopfront, and like seventeenth-century apothecaries, were involved in the on-site manufacture of their own medicines. They also took on an advisory role for those members of the lower and middle classes who could not afford the expensive care of a physician, but who were literate in the kinds of drugs needed to treat minor ailments. The druggists were entrepreneurial as well as medical, businessmen as well as trained practitioners. They successfully saw and filled a gap in the market left by the transition of the surgeon-apothecary to general practitioner; namely, an opportunity to sell drugs cheaply and undercut the prices charged by this new rank-and-file physician.

The Physician's Verdict. Oil painting by Emile Carolus Leclerq, 1857. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection (CC).

Unsurprisingly, a rivalry developed between the apothecary-GPs and the chemist-druggists over professional turf, particularly in regard to dispensing physicians' medicines. The apothecary-GPs’ desire to establish professional distinction led to agitation for legal reform and, eventually, to legal regulation of the medical community. Between the 1815 Apothecaries Act and the 1858 Medical Act, the practice of medicine became regulated in Britain. Apothecaries became subject to rules regarding training, licensing, and practice. Chemists and druggists were excluded from this licensing, but defined as a distinct profession with their own jurisdiction. Towards the middle of the century, they began pushing for their own regulatory body in order to prevent charges of quackery, and reinforce their medical status. This culminated in the founding of the Pharmaceutical Society in 1841. Schools were then set up to teach pharmacy, and the Pharmacy Acts of 1852 and 1868 helped to regulate the sale of pharmaceuticals, and create uniform standards of training and examination. However, not all chemists and druggists educated themselves in this way, and many continued to learn the ropes via apprenticeship until late in the nineteenth century.

Victorian Apothecary Costume Ideas

By the mid-1800s, the English chemist and druggist were well-established professionals, defined by their work in a wholesale and retail capacity, and catering to a population before, instead of, or in addition to, the intervention of a GP. Their services were wide ranging and competitive; they sold a variety of items, from toiletries and food to ointments and pills, and were appealing to a paying customer who (at least in the cities) had a choice of establishments to patronise. Despite this, many succeeded in making an excellent living, and had a high standing within their communities. Broadly, they functioned as a medical “first-port-of-call” for many different social classes.